IN THIS ISSUE

FOOD: The Kohala Center launches comprehensive school garden curriculum for Hawai‘i’s teachers

WATER: Why wai? Understanding the sources (and limits) of Hawai‘i’s water

PLACE: Local effort, global impact: MIT partnership will test new, low-cost air quality sensors

PEOPLE: Intellectual leadership for Hawai‘i’s future: The 2016–2017 Mellon-Hawaii Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellows

The Kohala Center launches comprehensive school garden curriculum for Hawai‘i’s teachers

While Hawai‘i’s keiki (children) were enjoing their summer vacations, school garden educators gathered in Kealakekua for four days to master our groundbreaking new teaching tool: the Hawai‘i School Garden Curriculum Map. As a result, many of Hawai‘i’s schoolchildren will deepen their engagements with core academic subjects, healthy food, and the natural world as educators start to use this comprehensive new resource for grades K-8.

The Hawai‘i School Garden Curriculum Map provides Hawai‘i’s K–8 educators with an integrated resource that connects classroom and garden instruction with state and federal education and health guidelines, including Common Core and Next Generation Science Standards.

Since 2007, The Kohala Center has recognized and worked to address Hawai‘i’s food security challenges. Preliminary research conducted in partnership with the Rocky Mountain Institute that year, further validated and refined by the 2012 Hawai‘i County Food Self-Sufficiency Baseline Study, estimated that 85% of the food available to Hawai‘i Island consumers is imported from at least 2,300 miles away. Over the years we have developed a long-term strategy to improve food security in Hawai‘i that includes increasing the demand for local food as well as inspiring and training future generations of island farmers and food producers. School gardens, which were abundant in Hawai‘i through most of the 20th century, gradually faded with the rise of imported food arriving on container ships and a shift to a visitor-industry economy. The availability of low-cost, processed foods led to less nutritious meals in schools and homes, contributing to a rise in childhood obesity.

We created the Hawai‘i Island School Garden Network (HISGN) to encourage the revitalization of school learning gardens to connect island keiki to fresh food, healthier eating habits, and the ‘āina itself. Through the program we have supported more than 60 public, private, and charter schools on Hawai‘i Island through technical assistance, mini-grants, and professional development programs; helped to launch the statewide Hawai‘i Farm to School and School Garden Hui; and serve as the host site for FoodCorps Hawai‘i. These initiatives work to develop school garden and nutrition programs; help schools procure fresh, healthy, locally grown food; and assist in the development of school wellness programs.

Attendees of the 2016 Kū ‘Āina Pā Summer Intensive gathered at Kona Pacific Public Charter School to learn how to use the Hawai‘i School Garden Curriculum Map.

In 2012 we launched Kū ‘Āina Pā, a school garden teacher-training and certification program for Hawai‘i’s school learning garden and classroom educators. More than 80 teachers from five islands have graduated from the yearlong program, in which they learn gardening skills and how to connect garden activities with classroom-based instruction in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

This summer’s Ku ‘Āina Pa gathering introduced our new Hawai‘i School Garden Curriculum Map to 30 K-8 teachers from Hawai‘i Island, O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, and the Marshall Islands. The Curriculum Map provides a consistent, centralized guide and set of tools that take a diverse set of lessons and curricula developed by local educators over the years and organizes them into four key themes: a sense of place, soils and plants, physical and mental nourishment, and natural systems. Teaching topics, garden activities, classroom extensions, and learning outcomes are defined within each theme and are mapped to Common Core, Next Generation Science Standards, Hawai‘i Health Standards, and STEM learning opportunities. A working group convened by The Kohala Center in partnership with Māla‘ai: The Culinary Garden of Waimea Middle School developed the Curriculum Map with support from the WHH Foundation, The Bill Healy Foundation, Hau‘oli Mau Loa Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm to School Program.

Teachers participating in the Curriculum Map training sharpened their garden instruction skills, including how to teach their students about the composition of soil.

“We believe our Hawai‘i School Garden Curriculum Map is a pioneering effort that aligns school learning garden curriculum and activities with state and national education and health standards,” said Nancy Redfeather, who helped us start HISGN in 2007. “This Curriculum Map was developed in collaboration with experienced classroom and garden educators for peers who may not be gardeners themselves, but intuitively understand the benefits of inquiry-based, place-based, project-based learning on academic performance and student wellness.”

Implementation of the Curriculum Map is expected to be most effective when garden and classroom instructors work together in grade-level teams. For example, fourth-grade teachers, a gifted and talented teacher, and garden educators at Kealakehe Elementary School will work together this year to ensure continuity between garden and classroom instruction. A similar team of educators at Kohala Elementary School will also test-drive the tool with third graders.

“The Hawai‘i School Garden Curriculum Map matches school standards with specific garden activities, giving teachers the tools and inspiration they need to teach their classroom subjects in the garden,” said Kayla Sinotte, a former FoodCorps Hawai‘i service member at Kohala Elementary who is now a part-time garden teacher at the campus. “I’m looking forward to collaborating with our teachers and our new FoodCorps service member to use the garden to its fullest potential to teach STEM and other topics.”

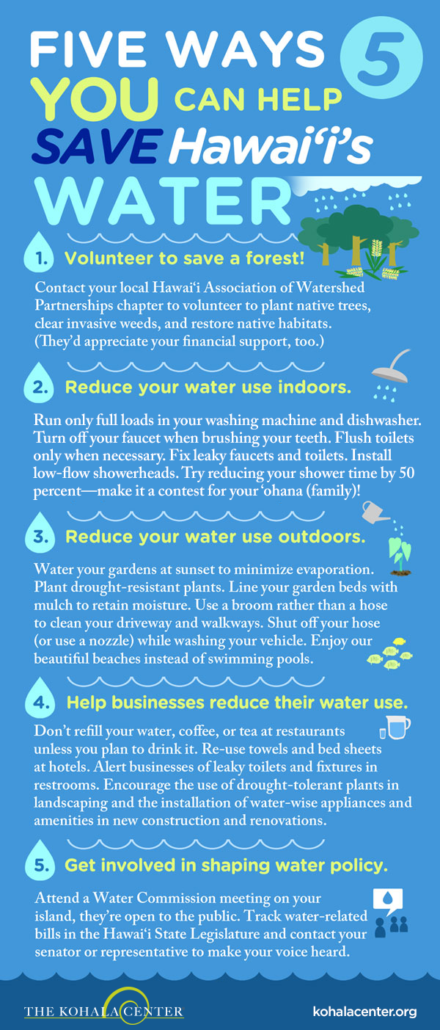

Why wai? Understanding the sources (and limits) of Hawai‘i’s water

It may seem like we have an endless supply of water here in Hawai‘i. Windward areas of some islands receive 120 to more than 200 inches of rain a year on average—considerably more than the “rainy city” of Seattle, which receives less than 40 inches per year. Population growth, changing land-use demands, deforestation, and climate change, however, pose significant threats to our water supply and even to rainfall itself. Fortunately there are many simple steps individuals and communities can take to save and protect water for Hawai‘i’s future.

Hawai‘i’s fresh water supply and ability to grow food depend on protecting and nurturing our native forests and watersheds. The health of our ocean and marine life relies on minimizing pollution, mitigating upland sediment runoff, and caring for our coral reefs. Through ecosystem protection and restoration projects, volunteer efforts, partnerships, and community engagement, The Kohala Center’s Kohala Watershed Partnership and Kahalu‘u Bay Education Center programs work to ensure Hawai‘i has an abundance of clean, healthy water from mauka to makai (mountain to sea).

“Hahai nō ka ua i ka ululāʻau” is a Hawaiian proverb meaning, “The rains always follow the forest.” Knowing this rule, Native Hawaiians took care not to harvest more trees or forest resources than were needed. Since the early 19th century, however, approximately half of Hawai‘i’s native forests have been lost due to development and industrial-scale resource extraction. As a result, Hawai‘i’s natural water cycles have been disrupted. Coupled with changes in global climate patterns and increased demands from growing business and residential communities, the need to preserve and support Hawai‘i’s sources of water may be more urgent than ever before.

After an unusually dry winter and despite periods of heavy rain this spring and early summer, the cities of Hilo, Kahului, Honolulu, and Līhu‘e experienced below-average rainfall the first half of 2016, and leeward regions of most of our islands are currently experiencing abnormally dry to moderate drought conditions. Residents, visitors, and businesses can do their part by taking small, easy steps to use less water and maintain an adequate water supply.

“Water is the essential natural resource that binds together all of The Kohala Center’s efforts in agriculture, ecosystem protection, and community health,” said Nicole Milne, our vice president for programs. “It’s important for everyone in Hawai‘i to understand our water cycles and systems and how we’re managing them today. Water is our most precious and vulnerable natural resource. We can’t afford to run out of water, because realistically there’s nothing to replace it.”

At The Kohala Center we believe we can all find inspiration to save water—and the planet—by understanding Hawaiians’ historical and cultural relationships with the environment. The traditional ahupua‘a (mountain-to-sea land division) system of natural resource management can perhaps be summed up as “take only what you need,” and our relationship with water should go much deeper than expecting it to be there when we turn on the faucet.

The Hawaiian word for wealth—“waiwai”—comes from “wai,” the Hawaiian word for water. For centuries Hawaiians have understood that water is the true source of life, abundance, and health. We must not take it for granted: we must understand where it comes from and nurture its sources. Our food, our communities, and our keiki depend on us to use only what we need to ensure Hawai‘i’s water resources remain healthy and abundant for generations to come.

Local effort, global impact: MIT partnership will test new, low-cost air quality sensors

As we continue to respectfully engage the Island of Hawai‘i as a model of and for the world, we are honored to collaborate with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to implement and test new, low-cost air quality sensors that could inform public health and pollution mitigation strategies in communities around the globe. The project will also provide island students with real-world opportunities to deepen their understanding of the physical sciences, technology, climate, and data analysis.

The portable air quality sensor nodes feature a small footprint and the ability to measure sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter levels. (Photo courtesy Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

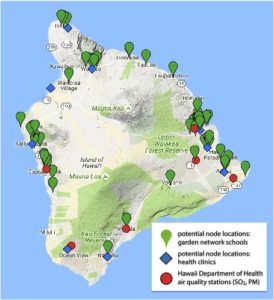

For the past 16 years one of the unique approaches of our work has been to recognize challenges to—and by—Hawai‘i’s natural environments as intellectual assets and learning opportunities. One such natural challenge that deserves greater scientific investigation is the effects of vog—the “volcanic smog” of sulfur dioxide and small particulate matter emitted by active volcanoes—on community health and agriculture. With grant funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and on-the-ground community engagement from The Kohala Center, MIT will develop and test a network of air quality sensors here on Hawai‘i Island to measure the impact of emissions from Kīlauea volcano and detect other compromises to overall air quality. We will assist with installing the sensors in school learning gardens and community health centers, and work with MIT faculty and staff to develop and deliver professional development training for secondary school teachers to use the sensors as teaching tools.

Modern technological advances are leading to the development of low-cost air pollution sensors, but they have yet to be widely tested under field conditions. Hawai‘i Island provides an ideal testing environment, given its mix of natural, uncontrollable emissions from Kīlauea and controllable particulate pollution from man-made sources. EPA grants are funding research to explore how scientific data can be gathered and used by communities effectively to understand the impacts of local air quality, and evaluate the accuracy of data produced by these new sensors as compared to established monitoring technologies.

A map of Hawai‘i Island showing locations of existing air quality stations and potential locations at school gardens and community health clinics. (Image courtesy Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

“MIT’s Hawai‘i Island Air Quality Network will augment existing air quality sensors on the island and provide researchers with opportunities to determine how well the sensors can distinguish between natural and human-generated particulate matter,” said Dr. Elizabeth Cole, interim president and chief executive officer of The Kohala Center. “By installing these sensors in school learning gardens around the island, our students will also gain real-world opportunities for place-based investigative research and learn how to use data for community benefit.”

Island residents have expressed interest in accessing more localized, real-time air quality data, and the Hawai‘i Island Air Quality Network will expand the number of existing sensors on the island from six to nearly 40. Professor Jesse Kroll of MIT’s department of civil and environmental engineering and department of chemical engineering has been impressed by the support that Hawai‘i Island residents have shown in learning more about local air quality. “The vog—how much there is, what it means for people’s health, and what people can do to minimize exposures—is a major concern, and we’re excited to provide a sensor network for community members to better understand their environment,” he said.

While vog cannot be controlled, more localized, real-time data can help people minimize their exposure to vog or man-made air pollutants, and help the public and their policymakers gain a better understanding of how controllable emissions affect local air quality and community health. If the sensor network proves successful, it will serve as a model for the implementation of similar networks in other communities around the world, particularly in rapidly growing urban areas with a variety of air quality challenges.

Intellectual leadership for Hawai‘i’s future: The 2016–2017 Mellon-Hawaii Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellows

The ninth cohort of Mellon-Hawai‘i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellows. (l-r) Dr. Kiana Frank, No‘eau Peralto, Kealoha Fox.

To chart a course toward a more resilient future for Hawai‘i, we must embrace the wisdom of Hawai‘i’s past. As the three Native Hawaiian scholars who make up the ninth cohort of our Mellon-Hawai‘i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program conduct contemporary research in the areas of agriculture and community health, they are carrying forward ancestral knowledge and practices that sustained Hawai‘i for generations.

The Kohala Center launched the Mellon-Hawaiʻi Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in 2008 with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Kamehameha Schools to recognize and support the work of emerging Native Hawaiian academics and others committed to the advancement of knowledge about Hawai‘i’s natural and cultural environment, history, politics, and society. To date, 35 Native Hawaiian scholars have pursued original research and advanced their academic careers through the program. Fellowships provide stipends and mentoring to enable doctoral fellows to complete their dissertations before accepting their first academic posts and to afford postdoctoral fellows the opportunity to publish original research early in their academic careers. The 2016–2017 cohort is supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Kamehameha Schools, and the Deviants from the Norm Fund.

The research topics being pursued by this year’s fellows, while diverse, all focus on supporting the health and well-being of Hawai‘i’s modern-day communities by examining and embracing ancestral knowledge and practices.

Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe and Kealoha Fox

Kealoha Fox is pursuing a Ph.D. in clinical research at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa). Her dissertation investigates uplifting health in Native Hawaiian communities by reconnecting with the traditional Hawaiian health system and revitalizing ancestral assessment, diagnostic, and treatment practices. Her mentor is Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe, ka pouhana (chief executive officer) of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and an experienced clinical psychologist.

Fox’s research is inspired in large part by her family and a genuine desire to contribute to positive health outcomes for Hawai‘i’s people. “When I look at my son, I am constantly reminded that the next generation of Native Hawaiians deserves improved health strategies that command positive systemic shifts and reinvest well-being back into our ‘ohana (families) and kaiāulu (communities),” she said. “By tracing our traditional practices of medicine and creating a comprehensive resource inventory, my research seeks to rebuild Hawaiian assessment and diagnostic processes that are largely absent from contemporary healthcare delivery.”

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua and No‘eau Peralto

No‘eau Peralto is a Ph.D. candidate in the indigenous politics program in the department of political science at UH Mānoa. A resident of Pa‘auilo, Hāmākua, Hawai‘i Island, Peralto’s research focuses on the continuity and resurgence of Native Hawaiian ‘āina restoration and stewardship practices in two ahupua‘a in Hawai‘i Island’s Hāmākua District. Through his research, Peralto seeks to contribute to deeper understandings of indigenous, place-based land tenure practices and governance structures as models of ea—community resurgence and independence. His mentor is Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, herself a Mellon-Hawai‘i doctoral fellow in 2010-2011 and associate professor of political science at UH Mānoa.

“My work is inspired by my kuleana (responsibilities) to my ʻohana, my community, and my kulāiwi (homelands),” Peralto said. “One of those kuleana is the telling of our moʻolelo (stories). Moʻolelo give birth to our values, beliefs, and practices, so it is important that we tell our moʻolelo of truth in ways that empower our people.” Peralto hopes to fill significant gaps in the historical records of Hāmākua and Hawaiʻi by retelling past and present moʻolelo of those who mālama ʻāina (care for the land) and aloha ʻāina (love the land) in the region, and evaluating how these accounts and efforts contribute to the resurgence of place-based mālama ʻāina systems and the enactment of sustainable self-determination in Hawaiʻi.

Drs. Kiana Frank and Davianna McGregor

Dr. Kiana Frank received her Ph.D. in molecular cell biology from Harvard University in 2013. Her postdoctoral fellowship will enable her to focus on manuscripts exploring the intersection of ancestral and contemporary science by investigating the biogeochemical drivers of microbial processes in Windward O‘ahu’s He‘eia Fishpond and correlating them to the pond’s cultural history and management practices. Frank is being mentored by Dr. Davianna McGregor, professor of ethnic studies at UH Mānoa.

“I study microbes in our ‘āina—who they are, what they are doing, and their importance in traditional management—to enhance the productivity, sustainability, and resilience of Hawai‘i’s aquacultural and agricultural resources,” Frank said. “I believe that science is an important tool in our community, not only to drive data-based policy, but to advance our understanding of our place and how we fit into that place. It is important to recognize that science is not separate from our culture and our identity, but rather that science is a strength of our indigenous culture.” Frank hopes that her work will help inspire a shift in how science is perceived in both indigenous and scientific communities by demonstrating how place-based knowledge and traditional management practices can complement and enhance contemporary technology and scientific knowledge systems.

Since its inception, the Mellon-Hawai‘i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program has awarded $1.48 million in fellowship support to 35 Native Hawaiian scholars. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which initially agreed to underwrite the program for three years, extended its support for two additional three-year periods. The 2016–2017 cohort represents the final year of The Foundation’s support.

“The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s investment in this fellowship program has had a profound impact not just on the lives of Native Hawaiian scholars, but on future generations of keiki who will be inspired by these intellectual role models to pursue meaningful careers and strive for excellence—for Hawai‘i and the world,” said Robert Lindsey Jr., a member of The Kohala Center’s board of directors and chairman of the program’s selection committee. “We are deeply grateful for The Foundation’s support over the past nine years, and we are hopeful that new partners will join with Kamehameha Schools and the Deviants from the Norm Fund and enable us to continue to offer these fellowships to Hawai‘i’s emerging intellectual leaders.”