By Dr. Matthews M. Hamabata, Executive Director, The Kohala Center

“That’s cool,” Maenette Ah Nee-Benham, Dean of the University of Hawai‘i’s Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge, and I found ourselves saying to a young girl who had just told us that among the careers she was thinking about was the field of marine engineering.

“That’s cool,” Maenette Ah Nee-Benham, Dean of the University of Hawai‘i’s Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge, and I found ourselves saying to a young girl who had just told us that among the careers she was thinking about was the field of marine engineering.

“Thank you,” she said. “We are studying idiomatic English.”

Needless to say, Maenette and I burst into laughter. Just another moment of sheer joy at witnessing and experiencing the optimism, the resourcefulness, and the push for excellence on the part of our colleagues in the Philippines, who are linking education with community development and the care of the natural environment as a way to alleviate poverty and achieve community well-being.

The young girl with aspirations to become an engineer is a participant in the Tuloy sa Don Bosco Streetchildren Village, which serves poor, orphaned and abandoned children in metropolitan Manila. The charismatic Father Rocky, who started the program with twelve children, now reaches 900 through a residential and day program in a beautifully designed campus, verdant with gardens, bright with murals, and ringing with happy voices and music. “You can’t tell a child she is important,” he said. “You’ve got to show her she’s important. That’s why our campus looks this way.” Looking at the immaculate and attractive school, it is difficult to comprehend that it was once an informal garbage dump for the city.

The commitment to excellence is evident everywhere, from the expectation that we would arrive on time to the well-executed campus plan, to the near-perfect English of our young guide, who was studying it as a second language. “We do not tolerate mediocrity,” commented Father Rocky, in a gentle but firm tone of voice.

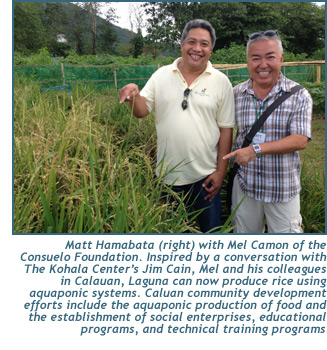

The delegation from Hawai‘i, which had been assembled by the Consuelo Foundation to visit with non-governmental organizations in the Philippines that were addressing societal well-being through their own versions of ‘āina-based programs, noted that the Tuloy sa Don Bosco campus was set within an urban farm, where ornamentals, as well as food for consumption and for sale, were being produced through an elaborate aquaponic system maintained by the students and staff. “How many pounds of food do you grow per month?” one of us asked.

The delegation from Hawai‘i, which had been assembled by the Consuelo Foundation to visit with non-governmental organizations in the Philippines that were addressing societal well-being through their own versions of ‘āina-based programs, noted that the Tuloy sa Don Bosco campus was set within an urban farm, where ornamentals, as well as food for consumption and for sale, were being produced through an elaborate aquaponic system maintained by the students and staff. “How many pounds of food do you grow per month?” one of us asked.

Father Rocky fixed his eyes on the questioner. “You are asking the wrong question,” he said. “You see, just as a child in distress cannot wait, the environment cannot wait. It is about the millions of green leaves that we grow here.”

The immediate need to mitigate the production of greenhouse gases is experienced in the rapid cycles of flooding in Manila, from which the poor, the “informal dwellers” on the city’s riverbanks, lose their homes and are dislocated and from which they die. Yes, the children in the school are learning about science, mathematics, engineering, aquaculture, and agriculture through their campus urban aqua-farm. Yes, they are linking their studies to issues of societal and global importance. And, yes, they are fighting for their lives.

In the faces of the young served by Father Rocky, I came to see and understand climate change as more than just an environmental issue. It is also a human rights issue. I began to understand at a visceral level that what we do for—or to—the environment in Hawai‘i affects the lives of communities around the world, in ways both immediate and dramatic.

As we were about to part company, about 100 children gathered in the school’s bright and airy gymnasium. The Hawai‘i delegation sat in the middle of the basketball court. And the children danced and sang for us. When they concluded with a rendition of an old Beatles tune,

Your song will fill the air

Sing it loud so I can hear you

Make it easy to be near you...”

there was not a dry eye among us.

We returned the gift by singing Peter Moon’s “Hawaiian Lullaby” with Kaipo Kukahiko and Kihei Nahale‘a on instruments and Maenette Benham offering a hula.

Over and over again during our visit to the Philippines, the human spirit was affirmed by the creativity, generosity, courage, resourcefulness, and artistry of our Filipino colleagues and the communities they serve. As an executive director of a nonprofit here in Hawai‘i, the experience further committed me to excellence, and it deepened my appreciation of the wisdom of island communities. For it was island communities that asked us to create greater employment and educational opportunities by caring for—and celebrating—Hawai‘i’s spectacular natural and cultural landscape. And it was island communities that moved The Kohala Center forward in addressing issues of food self-reliance, energy self-reliance, and ecosystem health, as ways to ensure community well-being and resilience.

I know that I speak for the entire Hawai‘i delegation when I say that I am grateful to the Consuelo Foundation for uplifting our spirits and allowing us the opportunity to further commit ourselves to our work for communities in Hawai‘i and around the world.

The revival of Kahalu‘u Bay

Over the years, the visitor count at Kahalu‘u Bay and Beach Park has swelled to over 400,000 people annually. The increased traffic, coupled with dwindling public maintenance resources, resulted in the bay’s corals being literally trampled to death and park facilities falling into disrepair. Fortunately, the dedication of volunteers, the formation of the Kahalu‘u Bay Education Center in 2011, and the support of the community are turning things around.

Over the years, the visitor count at Kahalu‘u Bay and Beach Park has swelled to over 400,000 people annually. The increased traffic, coupled with dwindling public maintenance resources, resulted in the bay’s corals being literally trampled to death and park facilities falling into disrepair. Fortunately, the dedication of volunteers, the formation of the Kahalu‘u Bay Education Center in 2011, and the support of the community are turning things around.

Kahalu‘u Bay Education Center (KBEC), a program of The Kohala Center in partnership with the County of Hawaii Department of Parks and Recreation, was created to facilitate a formal effort to heal the bay, educate visitors about the bay’s fragile ecosystem and cultural significance, implement a master plan to revitalize the park, and reconnect the bay with island residents.

“Kahalu‘u Bay can be considered the nursery of our coastal fisheries,” said Matt Hamabata, executive director of The Kohala Center. “After years of neglect, community and business leaders, school teachers, residents, and government agencies came to us for help.”

In 2006, The Kohala Center assumed the reins of ReefTeach, a volunteer program started by the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant program. And in 2011, The Kohala Center entered into a unique ten-year agreement with the County of Hawai‘i to maintain Kahalu‘u Beach Park and establish an on-site learning center. Today, KBEC’s staff and over 400 ReefTeach volunteers promote “reef etiquette” to visitors, reaching an estimated 52,000 park patrons annually. Another volunteer program, Citizen Science, monitors the bay’s water quality and tracks data in an online portal.

In 2006, The Kohala Center assumed the reins of ReefTeach, a volunteer program started by the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant program. And in 2011, The Kohala Center entered into a unique ten-year agreement with the County of Hawai‘i to maintain Kahalu‘u Beach Park and establish an on-site learning center. Today, KBEC’s staff and over 400 ReefTeach volunteers promote “reef etiquette” to visitors, reaching an estimated 52,000 park patrons annually. Another volunteer program, Citizen Science, monitors the bay’s water quality and tracks data in an online portal.

“Did you know corals are living animals?”, reads a poster at KBEC. “If you must stand, choose a sandy area.”

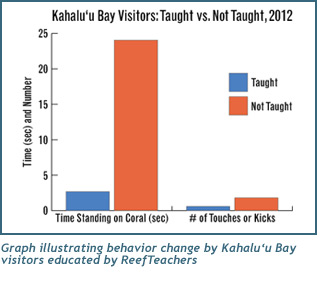

ReefTeachers, KBEC staff, and community leaders are committed to bringing Kahalu‘u’s vibrant coral reefs back to health after decades of damage wrought by swimmers and snorkelers. “We know that no one who visits here intends to cause harm,” said Cindi Punihaole, KBEC program director. “People simply don’t know that standing and stepping on the reef can kill the corals. They do, however, want to be responsible and do the right thing, so we offer face-to-face education on the beach and in the water, in a friendly and helpful manner. And our observations show that with a little knowledge and aloha, the behavior change is immediate and significant.”

Visitors’ behavior change is making a difference: while coral growth is very slow and will take years of data to measure, residents and visitors are noticing the positive effects of KBEC’s work. A KBEC supporter recently noted on the center’s Facebook page, “We have been snorkeling at the bay for 20 years now. Oh, how we have noticed the corals coming back! And all the baby fish. It is a direct result of the education you provide to [visitors] snorkeling in the bay. Keep up the good work!”

Visitors’ behavior change is making a difference: while coral growth is very slow and will take years of data to measure, residents and visitors are noticing the positive effects of KBEC’s work. A KBEC supporter recently noted on the center’s Facebook page, “We have been snorkeling at the bay for 20 years now. Oh, how we have noticed the corals coming back! And all the baby fish. It is a direct result of the education you provide to [visitors] snorkeling in the bay. Keep up the good work!”

KBEC also rents snorkeling gear and sells underwater cameras, eco-friendly sunscreen, educational guides, postcards, and notecards, with all proceeds going directly back into education and maintenance programs. All of the center’s gear, tents, tables, educational materials, and merchandise are housed in a small van, which is, as KBEC manager Jean BevanMarquez describes it, “busting at the seams.”

“Our holding capacity is maxed out!” says BevanMarquez. “Every day that we unload and load the van, we marvel at the fact that it somehow all fits. But as visitorship grows, so does demand for snorkeling equipment, volunteers, and workspace. We need to expand our facilities to serve our guests, educate them on how to be good stewards, and ensure they all have an enjoyable visit.”

To meet the demand for greater capacity, The Kohala Center and KBEC need to raise $150,000 in the next twelve months to replace the van with a semi-permanent trailer that will provide more storage space and allow staff to serve more visitors, as well as a pickup truck that can tow the trailer in the event of a tsunami or hurricane.

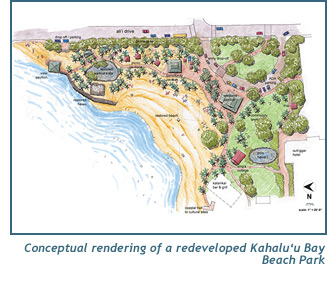

The long-term vision is to implement a Master Plan to redevelop the park’s facilities. “The Master Plan will include input from the surrounding community, from kūpuna (esteemed elders) all the way down to keiki (children),” Punihaole said. “We want to create a gathering place for local families and visitors that is safe and welcoming, while also promoting reverence and respect for our environment and wildlife. Hanauma Bay on O‘ahu has done a great job in steering all visitors through their educational program before entering the bay, while ensuring the site is accessible to state residents. It’s a model we’d like to emulate—for the sake of the bay and the community.”

The Master Plan is expected to take years—and millions of dollars—to develop and implement. But Punihaole is undaunted and believes KBEC’s goals are reachable.

The Master Plan is expected to take years—and millions of dollars—to develop and implement. But Punihaole is undaunted and believes KBEC’s goals are reachable.

“We’re not planning an elaborate, concrete and glass visitor center, but a low-key, open structure that shares nature and reflects the values of our local families,” Punihaole said. “Our plan is pono (balanced, proper) because we are working with intent and with a passionate base of local businesses and residents. This is what drives my desire to keep Kahalu‘u Bay healthy.”

In the meantime, re-engaging the local community is a top priority. In June, KBEC started a monthly photo contest, encouraging residents and visitors to submit their best wildlife photos from Kahalu‘u Bay. Kona resident Bo Pardau’s beautiful shot of a honu (green sea turtle) took first prize in the inaugural contest. The contest is open to residents and visitors, and the contestant who submits the best photo as determined by KBEC staff wins a prize. More information and entry guidelines are available at http://www.kahaluubay.org/contest.html.

A community Beach Clean-up Day, at which volunteers will pick up cigarette butts and other “microlitter” on the beach that can wash into the bay and harm marine life, is scheduled for Saturday, September 7 from 9:00 a.m. to noon. And in late October, KBEC will host a family fun day featuring a Keiki Fishing Derby at Kahalu‘u Fishpond. The historic fishpond, which was damaged in the wake of the 2011 tsunami, has been restored with the help of the County and over 100 volunteers, but is filled with invasive tilapia.

“We came up with the idea of a fishing derby as a fun way for kids to engage in a friendly competition while learning about Hawaiian culture and the environment,” Punihaole said. “Kids can win great prizes from Fair Wind, Patagonia, and Jack’s Diving Locker in categories like most fish caught and best costume. All of the tilapia that are caught will be given to Kona aquaponics farms, which will raise the fish for food while fertilizing their ponds. And Kahalu‘u Fishpond will be a lot cleaner at the end of the day. Everybody wins.”

Stay tuned for more information about the Keiki Fishing Derby in the next issue of The Leaflet.

The efforts of KBEC staff, volunteers, sponsors, and supporters are improving the health of Kahalu‘u Bay’s rich and colorful ecosystem. With a vision for the future, KBEC is fostering a Kahalu‘u Beach Park that will be a beloved and welcoming community gathering place for generations to come.

Want to make a difference for Kahalu‘u Bay? There are many ways you can help! Become a volunteer with ReefTeach or Citizen Science. Adopt-a-Day at Kahalu‘u Bay for your company or organization. Buy a beautiful gift at KBEC’s online store. Or support the Master Plan with a tax-deductible donation.

Mellon-Hawai‘i Fellowship Program welcomes sixth cohort of scholars

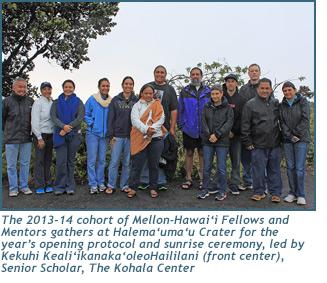

Five Native Hawaiian scholars will receive scholarly, peer, and financial support in 2013-2014 through the Mellon-Hawai‘i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Administered by The Kohala Center, the program aids scholars in producing original research and advancing their academic careers. The research being pursued by the program’s sixth cohort focuses on a unique and critical selection of Hawaiian literary, language, pedagogical, and political topics.

Five Native Hawaiian scholars will receive scholarly, peer, and financial support in 2013-2014 through the Mellon-Hawai‘i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Administered by The Kohala Center, the program aids scholars in producing original research and advancing their academic careers. The research being pursued by the program’s sixth cohort focuses on a unique and critical selection of Hawaiian literary, language, pedagogical, and political topics.

Doctoral fellowships were awarded to Eomailani Keonaonalikookalehua Kukahiko, Ph.D. candidate in Education; Bryan Gene Kamaoli Kuwada, Ph.D. candidate in English; Kaiwipunikauikawēkiu K. Lipe, Ph.D. candidate in Education Administration; and Iokepa Casumbal-Salazar, Ph.D. candidate in Indigenous Politics. All four of the doctoral fellows are enrolled at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Brandy Nālani McDougall, an assistant professor of American Studies at UH-Mānoa who earned her Ph.D. in English from the university in 2011, received a postdoctoral fellowship.

Doctoral fellows receive $40,000 each, and postdoctoral fellows receive $50,000 each. Each fellow works with a mentor, who is a leader in the fellow’s field of research. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and The Kohala Center established the fellowship program with support from Kamehameha Schools.

“I am deeply thankful and honored to have been selected as a 2013-2014 Mellon-Hawai‘i fellow,” said Lipe. “This opportunity allows me to support my family while also focusing full-time on completing my dissertation and graduating. I am also very grateful for the opportunities to learn and grow with past and present fellows, and be included in such a rich and vibrant family of leaders who are both scholars and practitioners. My goal is to emulate them and to build upon their work for the benefit of our lāhui (people).”

Since 2008, the Mellon-Hawai‘i Fellowship Program has assisted twenty-five doctoral and postdoctoral scholars early in their academic careers. The program fosters intellectual leadership by supporting scholars committed to the advancement of knowledge about the Hawaiian natural and cultural environment, Hawaiian history, politics, and society. The awards enable doctoral fellows to complete their dissertations before accepting their first academic posts, and provide postdoctoral fellows the opportunity to publish original research early in their academic careers.

“We are delighted and honored to support the work of Hawai‘i’s finest thinkers and writers,” said Dr. Matthews Hamabata, executive director of The Kohala Center and senior support staff to the Mellon-Hawai‘i Fellowship Program. “The Mellon-Hawai‘i Fellows have successfully established themselves as intellectual and educational leaders from Hawai‘i—for Hawai‘i and the world.”

Eomailani Kukahiko’s dissertation examines the experiences of mathematics teachers working in Hawaiian educational settings who successfully integrate Hawaiian language and culture into their curricula. She is being mentored by Joseph Zilliox, Ph.D., Professor at the Institute for Teacher Education in the College of Education at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Eomailani Kukahiko’s dissertation examines the experiences of mathematics teachers working in Hawaiian educational settings who successfully integrate Hawaiian language and culture into their curricula. She is being mentored by Joseph Zilliox, Ph.D., Professor at the Institute for Teacher Education in the College of Education at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Current literature indicates that the integration of culture and mathematics, or “ethnomathematics,” can increase student engagement in the classroom. “Initially, I was inspired to undertake this research topic as a teacher in Ka Papahana Kaiapuni Hawai‘i [the Hawai‘i Department of Education’s Hawaiian language immersion program],” Kukahiko said. “I was frustrated that the mathematics curriculum was merely direct translations of English texts. Knowing that my students and their families had chosen a Hawaiian language path of education, I felt a kuleana (responsibility) that every content area, including mathematics, should engage them through cultural content.”

Kukahiko’s research seeks to honor and harness Hawaiian knowledge and promote a deeper understanding of how Hawaiians viewed their mathematical environment. She hopes her work will inspire educators in all subjects to incorporate Hawaiian language and knowledge into their classrooms regardless of their educational setting.

Bryan Kuwada’s research focuses on the impact that translations had on Hawaiian history and the conveyance of that history today, as well as contemporary translation standards. His mentor is Craig Howes, Ph.D., Director of the Center for Biographical Research and a Professor in the Department of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Bryan Kuwada’s research focuses on the impact that translations had on Hawaiian history and the conveyance of that history today, as well as contemporary translation standards. His mentor is Craig Howes, Ph.D., Director of the Center for Biographical Research and a Professor in the Department of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

“My dissertation focuses on translation as a force that affected both how history played out in the kingdom and how we understand that history now,” Kuwada explains. “People often regard translation as a mechanical process, where a word or phrase from one language is switched with its equivalent from the other language. In truth, translation is a highly interpretive practice in which the translator is essentially acting as another author. Hawai‘i’s history is unique in that translation went both ways—with foreign stories, histories, treatises, laws, and such being translated into Hawaiian, and Hawaiian stories, histories, treatises, and laws being translated out of Hawaiian. My research also examines current translation practices, with the hopes of developing a more ethical and responsible model of translation than is often practiced now.”

Kuwada is hopeful that his research will connect—and reconnect—people to Hawaiian mo‘olelo (historical accounts), and influence translation practices that will ultimately make Hawaiian history and stories more relevant and accessible.

Kaiwipuni Lipe’s dissertation examines how the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa can achieve its strategic goal of becoming a Hawaiian place of learning. Her mentor is Maenette Ah Nee-Benham, Ed.D., Dean of the Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Kaiwipuni Lipe’s dissertation examines how the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa can achieve its strategic goal of becoming a Hawaiian place of learning. Her mentor is Maenette Ah Nee-Benham, Ed.D., Dean of the Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

“The number-one goal of UH-Mānoa is to ‘foster a Hawaiian place of learning,’” Lipe said. “However, the university is predominantly non-Hawaiian by almost every definition. My research explores how UH-Mānoa can implement this goal, given that its current culture and environment do not naturally support such a mandate. Because my work focuses on process—how we implement policies and goals specific to native Hawaiian and indigenous issues—I see my work benefiting Hawai‘i’s future by contributing to the dialogue of how we can actualize many of the written and approved policies and laws that sit on paper, but are largely ignored in practice.”

Lipe envisions her work benefiting Hawai‘i’s future by engaging with others to benefit the future of Hawai‘i’s people. She is committed to using the skills she has developed both in her academic career and her community to nurture and implement growing environments that foster native Hawaiian identity, knowledge systems, and practices.

Iokepa Casumbal-Salazar’s research analyzes the politics of astronomy-related development on Mauna Kea, the debates surrounding the planned eight-acre, eighteen-story Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT), and the legal opposition to continued development on the mountain. His mentor is Noenoe K. Silva, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Iokepa Casumbal-Salazar’s research analyzes the politics of astronomy-related development on Mauna Kea, the debates surrounding the planned eight-acre, eighteen-story Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT), and the legal opposition to continued development on the mountain. His mentor is Noenoe K. Silva, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

“My dissertation analyzes the discursive practices that shape debates around Mauna Kea astronomy, the TMT project, and opposition to them,” Casumbal-Salazar said. “I map several prominent discourses in which different ways of valuing Mauna Kea are constructed, enforced, and trivialized. Among other questions, my dissertation asks: What are the conditions of possibility for modern astronomy on the mountain considered sacred to many Kanaka ‘Ōiwi Maoli (Native Hawaiians)? As an intervention in conventional discourses that bolster—rather than question—structures of power and knowledge, my work offers a fuller understanding of the ways in which specific juridical encounters shape the contested meanings associated with Mauna Kea, ‘Ōiwi, science, nature, the sacred, and the good. My mo‘olelo seeks to contribute to the resurgence in aloha ‘āina (love/care for the land) and kuleana among our people.”

In approaching his dissertation, Casumbal-Salazar is mindful not to minimize the perspectives of astronomers, activists, or supporters and opponents of continued development. He seeks to expand the conversation about Mauna Kea astronomy and resistance to it by challenging the conventional narratives of the stakes involved for each side of the controversy, and by placing these narratives within the broader history of settler colonialism and U.S. occupation.

Postdoctoral Fellow Brandy Nālani McDougall’s monograph examines the continuity of the practice of kaona, a term often translated as “hidden meaning,” within contemporary Native Hawaiian Literature. She is being mentored by Cristina Bacchilega, Ph.D., Professor in the Department of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa .

Postdoctoral Fellow Brandy Nālani McDougall’s monograph examines the continuity of the practice of kaona, a term often translated as “hidden meaning,” within contemporary Native Hawaiian Literature. She is being mentored by Cristina Bacchilega, Ph.D., Professor in the Department of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa .

“Specifically, my manuscript examines kaona references to three of our Creation traditions—the Kumulipo, Papa and Wākea, and Pele and Hi‘iaka—and how our contemporary authors use kaona to emphasize our political and cultural claims to ‘āina (land) and lāhui, as well as our kuleana to enact those claims through decolonial action,” McDougall said. “I’ve been fascinated by our creation traditions and other mo‘olelo since I was very young. My parents, along with my kūpuna (esteemed elders), raised me with a deep love of mo‘olelo and reverence for the ‘āina, so mo‘olelo have been something we’ve long shared with each other as an ‘ohana (family).”

McDougall aspires to honor and recognize the intellectualism and spirituality of kūpuna through her writing, and demonstrate how their intellectual and spiritual contributions live on through Hawaiian literature, despite the cultural and environmental devastation caused by American colonialism. “Uncovering and interpreting these kaona elicit deeper connections to the ‘āina and our kūpuna,” she said. “Their lessons are infinite and tremendously healing. The kaona embedded within these mo‘olelo, coupled with the kaona being actively composed by contemporary authors, further hones and reinforces our intellectualism as a people.”

A distinguished panel of senior scholars and kūpuna assisted The Kohala Center in selecting this year’s cohort:

Panel Chair, Robert Lindsey, Jr., member, Board of Directors, The Kohala Center; and Trustee, Office of Hawaiian Affairs

Panel Executive Advisor, Dr. Shawn Kana‘iaupuni, director, Public Education Support Division, Kamehameha Schools

Dr. Dennis Gonsalves, former executive director, Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center; and Professor Emeritus, Cornell University

Dr. Pualani Kanahele, distinguished professor, Hawai‘i Community College and member, Board of Directors, the Edith Kanaka‘ole Foundation

Dr. James Kauahikaua, scientist-in-charge, U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

“The effect [of the Mellon-Hawai‘i Fellows Program] on our communities should not be underestimated,” said Dr. Noenoe Silva, who has served as a mentor in the program’s third, fifth, and sixth cohorts. “For many decades—the whole twentieth century, really—our Native Hawaiian children have grown up without intellectual role models. This is changing rapidly, in no small part due to this fellowship program. More Hawaiian professors means more Hawaiians entering higher education in every field, and that means more Hawaiian teachers at every level. The next generation of Native Hawaiians will grow up knowing that they can go to college and succeed if they wish, and go as far as they want to go because they see many other Hawaiians doing so. This represents incredible, important, and powerful change.”

The Kohala Center will support the progress of the five Mellon-Hawai‘i fellows in the coming year, bringing the fellows and their mentors together on Hawai‘i Island twice during the course of the program. The Kohala Center’s Circle of Friends is welcome to attend a public presentation of the fellows’ work on Saturday, November 9, 2013 at the Sheraton Kona Resort & Spa at Keauhou Bay. To RSVP or to learn about membership in The Kohala Center’s Circle of Friends, please contact Cortney Okumura at cokumura@kohalacenter.org or 808-887-6411.

An integrated and innovative approach to water issues

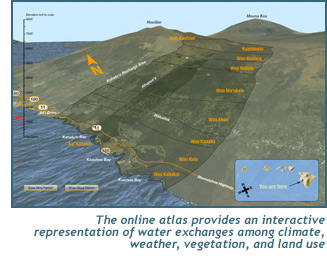

In accord with its mission to respectfully engage the Island of Hawai‘i as a model for humanity, The Kohala Center partnered with Hawaiian cultural experts, forest ecologists, hydrologists, economists, and geographic information science experts to create Waipuni Kahalu‘u, a new Web site that teaches users about the natural processes that contribute to the fresh water supply in the Kahalu‘u region on Hawai‘i Island.

In accord with its mission to respectfully engage the Island of Hawai‘i as a model for humanity, The Kohala Center partnered with Hawaiian cultural experts, forest ecologists, hydrologists, economists, and geographic information science experts to create Waipuni Kahalu‘u, a new Web site that teaches users about the natural processes that contribute to the fresh water supply in the Kahalu‘u region on Hawai‘i Island.

The Waipuni Kahalu‘u Web site (http://www.

spatial.redlands.edu/waipunikahaluu) represents a unique collaboration between the Edith Kanaka‘ole Foundation, the Watershed Professionals Network, the Redlands Institute, and The Kohala Center. At its core, Waipuni Kahalu‘u is based on Native Hawaiian knowledge.

“The overall goal of this project has been to connect people with the ‘āina through Hawaiian concepts and experiences,” said Matt Hamabata, executive director of The Kohala Center. “And to help people understand the consequences of their actions in a larger context.”

Focusing on the Kahalu‘u ahupua‘a (mountain-to-sea land division), the interactive site teaches users about the natural processes that contribute to the fresh water supply in the Kahalu‘u region.

Focusing on the Kahalu‘u ahupua‘a (mountain-to-sea land division), the interactive site teaches users about the natural processes that contribute to the fresh water supply in the Kahalu‘u region.

“Our leading partner, the Edith Kanaka‘ole Foundation, was willing and interested in sharing their knowledge,” Hamabata said. “We started with an immersion in the natural landscape, trust was built, and our group was able to bring together ideas and concepts from Hawaiian and Western knowledge systems.”

Funded by a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Sectoral Applications Research Program, Waipuni Kahalu‘u is based on Hawaiian knowledge and concepts of ecosystem health, which is then expressed through the vernacular of Western science and technology. The site offers an atlas of the Kahalu‘u ahupua‘a, a directory of Hawaiian terminology, and demonstrates how changes in climate and land use may affect essential fresh water systems. An interactive map section is an educational tool, which shows the potential impact of land use changes on groundwater.

The site also provides a glossary of relevant Hawaiian terminology, utilizing a Hawaiian methodology that segments the Hawaiian universe into three Papa (houses of knowledge): Papahulihonua, which includes knowledge of the natural environment pertaining to earth’s cycles; Papahulilani, knowledge about the atmospheric cycles; and Papahānaumoku, social, biological, and ecological knowledge pertaining to living organisms.

The site also provides a glossary of relevant Hawaiian terminology, utilizing a Hawaiian methodology that segments the Hawaiian universe into three Papa (houses of knowledge): Papahulihonua, which includes knowledge of the natural environment pertaining to earth’s cycles; Papahulilani, knowledge about the atmospheric cycles; and Papahānaumoku, social, biological, and ecological knowledge pertaining to living organisms.

The partners are grateful to NOAA for funding this dynamic and unique project, and for believing that both cultural experts and scientists can help communities anticipate and understand what might be happening with climate changes.

The creators of Waipuni Kahalu‘u consider it a work in progress—a place for the community to share knowledge, teach Hawaiian concepts, and link those concepts with photos, video, pronunciation, and other resources. The project team hopes that people use the site to more thoughtfully engage in the creation of infrastructure here in Hawai‘i. User input and feedback is welcomed and encouraged, and can be submitted via email to waipuni@kohalacenter.org.

Growing healthy keiki by growing school garden teachers

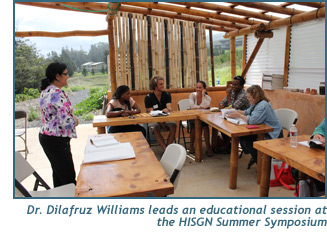

“The health of our children is directly related to the quality of their natural environment,” said Dr. Dilafruz Williams, keynote speaker at the sixth annual Hawai‘i Island School Garden Network Summer Symposium held in June. Over 120 people attended the event, held at Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy in Waimea.

“The health of our children is directly related to the quality of their natural environment,” said Dr. Dilafruz Williams, keynote speaker at the sixth annual Hawai‘i Island School Garden Network Summer Symposium held in June. Over 120 people attended the event, held at Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy in Waimea.

The symposium, “School Learning Gardens and Sustainability Education: Bringing Schools to Life and Life to Schools,” united classroom teachers, school garden teachers, administrators, staff, volunteers, and interested community members from around the state, as well as from Oregon, California, and Connecticut. It also included tours of six different school learning gardens in Waimea and culminated with a “Slow Food Lunch and Conversation” at Māla‘ai: The Culinary Garden of Waimea Middle School.

Also included in the symposium was the graduation ceremony for the first cohort of Kū ‘Āina Pā, a yearlong school garden training course. Kū ‘Āina Pā, which translates to “standing firmly in knowledge upon the land,” began its second year of training teachers after the symposium ended. The 26 teachers of Cohort One presented their research projects at the symposium and shared the knowledge, skills, and information they had learned.

Also included in the symposium was the graduation ceremony for the first cohort of Kū ‘Āina Pā, a yearlong school garden training course. Kū ‘Āina Pā, which translates to “standing firmly in knowledge upon the land,” began its second year of training teachers after the symposium ended. The 26 teachers of Cohort One presented their research projects at the symposium and shared the knowledge, skills, and information they had learned.

“Before the Hawai‘i Island School Garden Network (HISGN) was formed, everyone thought they were the only ones teaching this,” said Donna Mitts, HISGN program coordinator. “With this event, everyone’s morale is boosted. People have a chance to learn about valuable resources as well as come together to share and network.”

The goal of HISGN is to help island schools build gardening and agriculture programs that will significantly contribute to the increased consumption of locally grown food by involving students, their school communities, and their family networks in food production. HISGN supports school garden programs and educators by helping them identify funding opportunities and local agricultural resources, as well as by providing volunteer, curriculum, and professional development.

“It’s inspiring to work with teachers. To watch the growth this year has been amazing,” said Nancy Redfeather, HISGN program director. “I started teaching in 1969, and this year has been the best ever for me.”

The second cohort of Kū ‘Āina Pā began their summer intensive immediately after the symposium ended. In addition to pre-kindergarten through eighth grade teachers, this year’s intensive allowed teachers of 9th through 12th graders to participate. Funded in part by a USDA/SPECA “Ag in the Classroom K-12” grant, the program aims to build a unified school garden movement through mentoring, research, and curriculum development.

Some of the courses taught at the summer intensive included Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Concepts in the School Learning Garden, Nutrition: Seed to Seed, Best Practices of Organic Gardening Systems, and Linking School Gardens to Core Curriculum. After the intensive was over, many of the attendees expressed how teaching and learning in a garden-based context is “empowering, engaging, and rewarding for the students, teachers, and the community.”

Some of the courses taught at the summer intensive included Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Concepts in the School Learning Garden, Nutrition: Seed to Seed, Best Practices of Organic Gardening Systems, and Linking School Gardens to Core Curriculum. After the intensive was over, many of the attendees expressed how teaching and learning in a garden-based context is “empowering, engaging, and rewarding for the students, teachers, and the community.”

“I have never felt so aligned with a group of teachers ever,” said Cohort Two participant Mary Lynn Garner, a mathematics teacher at Konawaena High School. “Knowing that I am not hanging out there alone—which is easy to feel in my setting—but rather that I have an entire network of teachers and resource people available to me for all kinds of support has done a great deal to boost my confidence.”

Kea‘au High School environmental science teacher Ilana Stout, also of Cohort Two, said it was energizing for her to work with a group of educators who see the value in school gardening.

Kea‘au High School environmental science teacher Ilana Stout, also of Cohort Two, said it was energizing for her to work with a group of educators who see the value in school gardening.

“This is a powerful movement and our intentional sharing and co-creating is what moves the movement forward,” said Stout. “Dilafruz Williams’ description of modern education as ‘mechanistic’ really struck me: the dirty, messy, gloriousness of the natural world is simply inaccessible in institutional spaces.”

Dirty, messy, and glorious indeed! Supporting Hawai‘i Island’s school garden movement is easy. By volunteering or making a tax-deductible donation, you can further HISGN’s efforts to develop educators, promote local food production and childhood nutrition, and create engaging outdoor learning environments.